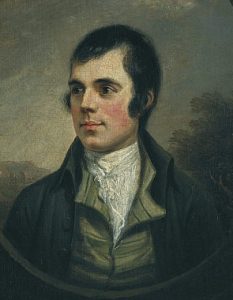

You can ascribe the writings of Robert Burns to virtually any subject. You can read his sense of delicacy and melancholy in any number of poems, just as you can deride his infidelity when you take into account his love life. But his universal appeal is no accident, his talent is no invention. Tonight is his 260th birthday.

Maybe you are giving your own version of the Bard at a Burns Supper somewhere. Is it Burns the farmer-poet or Burns the romantic wanderer? Are we going for the Burns of “Freedom an’ whisky gang thegither!” or is the mood more sober: Burns the Excise Officer. Whatever it is you are listening to, listen closely. If you’re reading about Burns in the media this week, read carefully. How much of it is real?

I am thinking about Sheilagh Tenant’s wonderful Rabbie Warhol (2009) and our many many interpretations of Burns. That well-ken’t face cast in a variety of colours is a lovely and simple way of saying that Burns is for all of us, whether or not we like what the other person is saying. But with such cultural power comes great contention. The same Burns who lamented the Union in these famous lines

But pith and power, till my last hour,

I’ll mak this declaration;

We’re bought and sold for English gold-

Such a parcel of rogues in a nation!

was used to recruit young men during the First World War. The poster quotes from the youthful piece ‘I’ll go and be a sodger’ (1782), suggesting

What Burns said 1782

Holds Good in 1915

Take his Tip.

You might also remember the (mis)use of Burns in the build up to Indyref 2014. Badges and coasters with his face were on sale: ‘Rabbie would say Aye!’ and ‘YES 2014: It’s coming yet for a’ that’. On the other hand The Daily Telegraph ran a front-page image of a saltire and union flag held proudly with the Edinburgh skyline in the distance. Burns’s lines from the song ‘The Dumfries Volunteers’ (1795) – ‘Be British still to British true, amang ourselves united’ – were featured there. In all honesty we would be as well placed guessing which football team he would support (a century before they were established) as his political allegiance.

There are more innocent examples. Just this week a headline read ‘Tesco’s vegan haggis “would make Robert Burns scoff.”’ The quote comes from Douglas Scott, chief executive at the Scottish Federation of Meat Traders. Now, unless Mr. Scott has a time machine or an eighteenth-century palette we can only assume his remarks were tongue-in-cheek. Or can we?

There are more innocent examples. Just this week a headline read ‘Tesco’s vegan haggis “would make Robert Burns scoff.”’ The quote comes from Douglas Scott, chief executive at the Scottish Federation of Meat Traders. Now, unless Mr. Scott has a time machine or an eighteenth-century palette we can only assume his remarks were tongue-in-cheek. Or can we?

The power of all this is the accumulation of assumptions. The clamour and the guessing games are more than likely off-putting to the would-be-reader of Burns’s actual works. This is where we get to the notion of truth vs. myth: an inseparable dance in the world of Burns which no other writer in the world comes close to (that’s right Shakespeare, I’m talking to you).

We could go back to the first ever Burns Supper, held in the poet’s birthplace in Alloway on 21 July 1801, exactly five years after Burns died. From this moment on Burns’s cult-hero status was constructed. Throughout the nineteenth century Burns Clubs were established and statues were built all over the world. Tourists went in search of some artefact, some fragment of Burns. One of the most intriguing memorials can be found in Atlanta, GA, where in 1911 the Burns Club there finished building a replica of the Bard’s birthplace cottage.

As our National Poet the presence of Burns is felt all the way from our primary schools to our national institutions. And with an annual festival of recitation and celebration, the Bard remains ‘immortal.’ In my career as a researcher and lecturer my focus on the eighteenth century reminds me (more often than I’d like it to) that none of us are immortal. The books on the shelves in my office are those of long-dead writers still telling their stories. The upside of this, of course, is getting the opportunity to really study their work and to see what the next generation makes of it all.

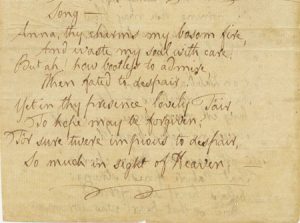

As regards Burns, here in the Centre for Robert Burns Studies, we are working towards a multi-volume edition of his works for Oxford University Press. At the moment my job is to trawl through Burns’s letters and to make notes on how they’ve been collected, edited and bowdlerized over the centuries. It is a team effort, with experts looking at all aspects of Burns’s output. But even with all the evidence and the resources of the twenty-first century to hand, combatting myth can be nigh impossible. A few examples…

First and foremost we are obliged to dispel the myth that Burns was some heaven-taught, uneducated vessel of pure genius. Burns was religious, but he was also well-educated. His reading of the philosophies of the Scottish Enlightenment and his participation in debating and fraternal societies come across clearly in his letters. This doesn’t quite fit the popular image of Burns at the plough found in the engravings of nineteenth-century editions.

But we cannot lay all the blame at the doors of the old editors, as enthusiastic about promoting Burns’s qualities as a man as they were about preserving the truth. If you examine the title-page of Burns’s first book, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (1786) you will read:

The Simple Bard, unbroke by rules of Art,

He pours the wild effusions of the heart:

And if inspir’d, ’tis Nature’s pow’rs inspire;

Her’s all the melting thrill, and her’s the kindling fire.

It is signed ‘Anonymous’, but this is unmistakably Burns. In the Preface, the same pen promises us that the author is “unacquainted with the necessary requisites for commencing Poet by rule”. And so the learned men and women of Edinburgh took Burns at his word, and he became a darling of high society.

As with most myths we circle back to the road less travelled. What if Burns hadn’t published his book, what if he’d run off with Highland Mary?

In recent years Scotland’s national identity has been under an incredibly bright light. We are often seen as a progressive, inclusive nation straining under the stress of an unhappy marriage to the rest of the UK. But we are also facing up to hard truths. The recent fervour around Scottish slave trading has epitomised a great awakening from the nightmares of our history. Many of you will guess where I’m going with this.

In recent years Scotland’s national identity has been under an incredibly bright light. We are often seen as a progressive, inclusive nation straining under the stress of an unhappy marriage to the rest of the UK. But we are also facing up to hard truths. The recent fervour around Scottish slave trading has epitomised a great awakening from the nightmares of our history. Many of you will guess where I’m going with this.

In the weeks before Burns’s debut work was printed he was on the cusp of travelling to Jamaica to find a living. Many Scots found work on the slave plantations there, and for Burns it seemed more likely than thriving at home. Of course, it didn’t happen. His Poems were published and he was an instant success. Ever since we have asked, what if? Most Burnsians would like to believe he would be a diligent bookkeeper, kind and even helpful to the indentured slaves. But how can we really know? How can we pin our hopes on a parallel universe? The song ‘The Slave’s Lament’ (1792) is only proof of his sentiments, which, as we know, can be applied to any number of contexts. As Prof. Gerard Carruthers has pointed out (twice) in public lectures we cannot hold up ‘The Slave’s Lament’ in the one hand and hide, with the other hand, ‘the coward slave – we pass him by’ (from ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ that.’)

Last year Prof. Murray Pittock’s The Scots Musical Museum (vols. 2 and 3 of the new Oxford edition) laid out 8 Categories by which to edit Burns’s songs, ranging from I – ‘A song wholly by Burns’ to VIII – ‘A song in which Burns had no hand.’ Many were shocked that Pittock removed 50 songs from the Burns canon. Among these were many beloved airs, and the popular song ‘O my luve’s like a Red, red rose’ was noted as being ‘heavily edited’ by Burns rather than the original many have taken it to be. In the wake of this we learned that casting Burns as a talented and skilled editor and curator of Scottish song culture is one thing, but undoing the entrenched Burns story, even for the better, is another.

Last year Prof. Murray Pittock’s The Scots Musical Museum (vols. 2 and 3 of the new Oxford edition) laid out 8 Categories by which to edit Burns’s songs, ranging from I – ‘A song wholly by Burns’ to VIII – ‘A song in which Burns had no hand.’ Many were shocked that Pittock removed 50 songs from the Burns canon. Among these were many beloved airs, and the popular song ‘O my luve’s like a Red, red rose’ was noted as being ‘heavily edited’ by Burns rather than the original many have taken it to be. In the wake of this we learned that casting Burns as a talented and skilled editor and curator of Scottish song culture is one thing, but undoing the entrenched Burns story, even for the better, is another.

This is not the first time that scholarly rigour has been met with alarm or even contempt, and I’m sure it won’t be the last. Myth and memory are a happy pair with Burns. But maybe that’s okay. In truth I am grateful that Burns has endured the centuries and that his wisdoms have echoed through the hearts of his readers.

My steady favourite is his conversation with the mouse, and his humble jealousy that the sleekit, cow’rin, tim’rous beastie lives only in the present while man, destined to fret and worry, thinks back in pain and plans forward in vain.

So let us charge our glasses and raise them to the imperfections of our society, to the promise that we can do better for one another, to get out of the trenches of our own ideas and share our truths as well as our myths.

#TaeTheBard

Craig Lamont is a Research Associate on two major AHRC-funded projects at the University of Glasgow, each of which will see the production of new multi-volume editions of the Works of Robert Burns and Allan Ramsay. Craig’s PhD thesis on ‘Georgian Glasgow’ won the 2016 Ross Roy Medal.

Craig Lamont is a Research Associate on two major AHRC-funded projects at the University of Glasgow, each of which will see the production of new multi-volume editions of the Works of Robert Burns and Allan Ramsay. Craig’s PhD thesis on ‘Georgian Glasgow’ won the 2016 Ross Roy Medal.