Far Distant, Far Distant: Orwell, My Father and Catalonia

Willy Maley

“Far distant, far distant, lies Foyers the brave/

No tombstone memorial shall hallow his grave/

His bones they lie scattered on the rude soil of Spain/

For young Jamie Foyers in battle was slain.”

The words of a well-known song, Jamie Foyers, written, or rather rewritten, by Scottish folk singer Ewan MacColl. Jamie Foyers was originally a song about a Scottish soldier, a Perthshire militiaman from Campsie who transferred to the Black Watch and was killed by a cannonball.

This was in 1812, in Burgos, Spain, during the Peninsular Wars. The song itself dates from the 1850s. Ewan MacColl’s mother Betsy had often sung it. Her son updated it and made it the tale of a fictional Clyde shipyard worker slain in Republican Spain.

For a long time, the original Jamie Foyers was thought to be a fictional character himself until recent records revealed a Sergeant James Foyer of the Black Watch listed among the casualties in Spain two hundred years ago – killed fighting the French under the Duke of Wellington. Human remains have been found on the site of his death.

Far distant, far distant. Yet there are still some people who think MacColl’s Jamie Foyers was real. It’s a myth perpetuated in Stuart Christie’s excellent book, Granny Made Me An Anarchist (2002), where he writes: “Another young Scot who left Glasgow to Spain to fight against Franco was Jamie Foyers, whose story was told in song by Ewan MacColl”. Christie tried to kill Franco in 1964, so mucho respect. But he was wrong about Foyers.

Many real Scots fought and died in Spain in the 1930s, but young Jamie Foyers wasn’t one of them. His death was far distant. Songs rewrite history, and so do historians.

“Far distant, far distant” is a refrain that’s been going through my head this past few weeks. How far distant are events in Catalonia from events in Spain eighty years ago? I have a family connection rather than a scholarly one with the Spanish Civil War, and I tend to view things through that particular lens. That family connection is with a father who had a lifetime of commitment stretching across a century, and whose obsession with politics was always firmly rooted in the present.

“Far distant, far distant” is a refrain that’s been going through my head this past few weeks. How far distant are events in Catalonia from events in Spain eighty years ago? I have a family connection rather than a scholarly one with the Spanish Civil War, and I tend to view things through that particular lens. That family connection is with a father who had a lifetime of commitment stretching across a century, and whose obsession with politics was always firmly rooted in the present.

My father fought for a socialist republic in Spain but died in a right-wing monarchy. There are those still fighting for a socialist republic – Spanish or Scottish or Catalan.

Far distant, far distant. It’s a long way from the mean streets of Glasgow’s East End to the playing fields of Eton but history is full of strange bedfellows. George Orwell shared with my father, James Maley, the experience of fighting in Spain in 1937, Orwell as a member of POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista) and my father as a member of the Communist Party.

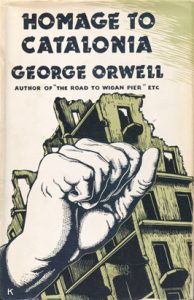

They had something else in common – an experience of empire. Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal in 1903. My father served in India during the Second World War. Both men also served in Burma, Orwell as a policeman in 1921; my father as a soldier twenty years later, drinking water from the Irrawaddy River while dead bodies floated past. At the end of Homage to Catalonia, Orwell bemoans the impossibility of agreement with a Communist Party member who would toe the party line in the teeth of unpalatable truths.

But Orwell qualified his comments: “Please note that I am saying nothing against the rank-and-file Communist, least of all against the thousands of Communists who died heroically round Madrid … those were not the men who were directing policy”. Despite this caveat, for too long Orwell’s elegant intervention and anti-Stalinism, appropriated during the Cold War as anti-communism, has been seen as an unanswerable case rather than a contingent document. Other views – including those of the many volunteers who wrote of their experiences, as well as those who told their tales without publishing their memoirs – have been side-lined and silenced.

At the end of Homage to Catalonia, Orwell declares: “The only hope is to keep political controversy on a plane where exhaustive discussion is possible”. This hope is crucial when it comes to events unfolding in Catalonia today. When Orwell told Arthur Koestler that “history stopped in 1936”, he had in mind that history had ended as a story that could be told with any semblance of truth, given the pervasive power of propaganda. Orwell knew the power of fake news. He had been an eyewitness to events that were in his view blatantly misreported.

At the end of Homage to Catalonia, Orwell declares: “The only hope is to keep political controversy on a plane where exhaustive discussion is possible”. This hope is crucial when it comes to events unfolding in Catalonia today. When Orwell told Arthur Koestler that “history stopped in 1936”, he had in mind that history had ended as a story that could be told with any semblance of truth, given the pervasive power of propaganda. Orwell knew the power of fake news. He had been an eyewitness to events that were in his view blatantly misreported.

When Glasgow was European City of Culture, I wrote a play with my brother John called From the Calton to Catalonia. It was based on the experiences of our father, imprisoned in Salamanca after his machine gun company was captured at Jarama in February 1937. The play, like MacColl’s song, takes poetic licence. One of the characters, Jamie, dies in Spain, like that far distant fellow Foyers, but our own father James came home. A line in the play has a woman worrying about her husband off fighting Franco say: “Spain, it’s that far away.”

It was further away in 1936 than it is today. Years later, I read an essay by Paul Preston, the leading authority on Spain, that suggested the Spanish Civil War was, in fact, a colonial conflict. According to Preston: “the right coped with the loss of a ‘real’ overseas empire by internalizing the empire … by regarding metropolitan Spain as the empire and the proletariat as the subject colonial race”. It was a civil war, a colonial war, and a revolution.

In an article in The Guardian on 7th May of this year, Preston observed: “Eighty years ago this week, the Ramblas of Barcelona echoed with gunfire. Much of what happened on the streets during the May days is well-known thanks to George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, but not why it happened.”

Preston calls Orwell’s book “another nail in the communist coffin, despite its distortion of the Spanish situation.” But Orwell can be seen in a different light, as Preston himself acknowledges. In July 1937, Orwell wrote: “The International Brigade is in some sense fighting for all of us – a thin line of suffering and often ill-armed human beings standing between barbarism and at least comparative decency.”

In The Lion and the Unicorn, Orwell lamented the fact that “England is perhaps the only great country whose intellectuals are ashamed of their own nationality.” Maybe he was just a petty-bourgeois nationalist at heart? Or perhaps he saw that the failure of the English Left to grasp the nettle of nationalism would open the door to xenophobia? In fact, Orwell was writing in the tradition of Milton, Blake and Shelley, and his insights have been taken up by Billy Bragg, who has also argued for an independent English republic, free from the baggage of empire. Orwell’s various observations on English and British identity are salutary in the current context.

There is a fault-line running through the European Left around the national question and the right of nations to self-determination. Marx, Engels, Lenin, James Connolly and John Maclean might have imagined they had settled the question over a century ago, but there is still a section of the socialist international that condemns what it sees as “nationalism”, often blind to their own attachment to lop-sided political unions or multi-nation states in which a single nation dominates.

This fault-line partly explains the complex and conflicting reaction to current events in Catalonia. The heavy-handed and entirely unjustified actions of the Madrid regime are deeply disturbing, and there are troubling echoes and shadows of the Franco era. Yet in Scotland, where the Left’s response to the threat of fascism in Spain eighty years ago is the stuff of legend, the reaction to current Catalan claims to independence has been mixed. There’s something haunting about Spain for Scots and for the Left, something “far distant”, yet ever-present. The culture of commemoration and the rhetoric of remembrance, the tendency towards nostalgia and sentiment, are a world away from today’s shifting and shifty headlines and the confusing swirl of social media. Catalan independence, like Scottish independence, divides the Left. It’s inevitable then that some of those with an interest in Spain that is chiefly historical, rooted in the later 1930s, may struggle to take sides today. For some, the defence of the Spanish Republic in 1936 means that the unity of Spain is essential and fragmentation is to be feared. Others, aware of the earlier efforts of Catalonia to achieve independence, might argue that what’s happening now is a return to the journey towards full autonomy derailed by Franco.

As a supporter of Scottish independence, I have no trouble supporting Catalonia’s case for independence, but I recognise the dilemma facing others. In 1936, Franco was the nationalist, the figure of unity. Crushing Catalan aspirations was one of his key aims. That, and ending the Republic. The Spanish socialists and republicans who had persuaded their comrades in Catalonia to hold fire on independence for the greater good then had to face up to a fascist future that lasted forty years. The transition to democracy entailed a break with dictatorship, but, as with all civil wars, the waters run deep and with the second and third generation come awkward questions about the legacy of fascism and the limits of transition.

The right of nations to self-determination cannot be curtailed by force, or by enforced forgetfulness, or by an appeal to internationalism that is incapable of nuance. Catalonia has been on the road to independence for a very long time, a road blocked by Franco eighty years ago, and a road that has now been radically shortened. The civic, constitutional and peaceful process in Catalonia has been exemplary, and despite the Spanish state’s resort to brutal tactics that have shocked the world and shamed Madrid, Catalonia remains a model of an aspiration to independence pursued with integrity and dignity. Scotland has been on a similar – not identical – road, and has also had to cope with a central government eager to close down debate, but in far subtler ways. The independence movement in Scotland is a constant and growing reality now, and needs no other stimulus, but events in Catalonia do remind us all of the need for a balanced, measured and restrained approach on all sides. Solidarity with other aspirations to independence is crucial. Overhasty analogies are unhelpful, of course, but comparisons, if convincing, can be instructive. Rising above the foul play and dirty tricks of a centralising and controlling state calls for smart thinking and careful reflection. It means keeping informed when the mainstream media fails to cover events in the many-sided way required of serious political analysis. It means taking stock and learning from others. Catalonia and Caledonia have some shared history – as the Scots who fought Franco attest – and they have shared aspirations too for a more just society. Encountering obstacles to independence is inevitable – it’s how we deal with those roadblocks that matters.

Far distant, far distant. The more time passes the closer history gets. As the last members of the International Brigades pass away, there’s a sense of brushing the coattails of history. The Spanish Civil War is still an open book – and an open sore. Despite innumerable studies of causes, courses, consequences, it’s too early to say what happened between July 1936 and April 1939. Spain remains a crucible of conflict for critics and combatants. Only now in the last light of living memory is the serious business of truth and reconciliation underway. But that process has been interrupted. The fallout from Franco and fascism lingers on. The unfinished business of Catalan independence is back on the table. History is here again.

I started with a song and I’ll end with another. In 1965, American satirist and polymath Tom Lehrer parodied Glaswegian Alex McDade’s by now famous Jarama Valley song, itself adapted from a much older folk song, Red River Valley:

“Remember the war against Franco?

That’s the kind where each of us belongs/

Though he may have won all the battles/

We had all the good songs.”

Willy Maley is professor of English Literature at the University of Glasgow. He is co-author, with his brother John, of From the Calton to Catalonia, a play based on the experiences of their father, James Maley, who fought with the International Brigades. The play was recently reprinted by Calton Books.

Willy Maley is professor of English Literature at the University of Glasgow. He is co-author, with his brother John, of From the Calton to Catalonia, a play based on the experiences of their father, James Maley, who fought with the International Brigades. The play was recently reprinted by Calton Books.