It wasn’t until Donald Trump was elected president of the US in November 2016 that a little more attention in that country was paid to his mother, Mary Trump. His attacks on immigrants had attracted many who had pointed out his own family’s immigration history: his paternal grandfather, Friedrich Trump, who came to the US from Kallstadt in Germany in the late nineteenth century aged sixteen; and his mother, Mary Trump nee Macleod, who left Lewis in 1930 at the age of eighteen for New York.

But it was Friedrich who triumphed in newspaper coverage, just as he had in the many, many biographies devoted to Trump well before even his grandson’s election campaign, never mind its result. From Gwenda Blair’s 2000 biography, The Trumps, to more recent ‘definitive’ biographies like Kranish and Fisher’s Trump Revealed and David Cay Johnston’s The Making of Donald Trump, the ‘family history’ of Donald J. Trump has been dominated by the stories of a father and a grandfather, led in that direction perhaps, by the man himself. In 1987, Trump: The Art of the Deal appeared in which he declared, “The most important influence on me was my father, Fred Trump.”

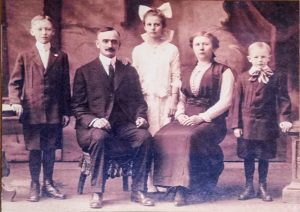

And so, given such a lead, biographers began chasing the father-son story, delighting when they could expose easy mistakes (in The Art of the Deal, Trump wrongly insisted his grandfather Friedrich came to the US from Sweden as a child), and relishing the gritty details of Friedrich’s hand-to-mouth existence on the Klondike, or his son Fred’s shady wartime deals over housing complexes. They told, and told again, a patrilineal story that excluded or at best side-lined the Trump women: Elizabeth Christ Trump, Trump’s grandmother, who kept the family business going when her son Fred was just a child and her husband died suddenly; Trump’s great-grandmother, Katherina, who found herself widowed young as well, when her son Friedrich was just eight.

These women worked hard; they brought up children with a work ethic based, in Katherina’s case, on working in the fields, baking bread to sell, or in Elizabeth’s, making money from sewing to keep the family real estate business going. When Trump’s mother, Mary, arrived in New York in 1930, it was to work as a domestic servant, an often backbreaking job she did for several years, before she married Fred Trump. Domestic work was hard, even in the 1930s with more domestic appliances to help: James M Cain’s 1941 novel, Mildred Pierce, showed a divorced single mother struggle desperately through the Depression, but even she didn’t want to take on live-in, domestic work. It was the worst paid and the hardest-grafting.

Yet, before Trump’s clinching of the 2016 presidency, few were even aware of his mother’s past. Biographies glossed over Mary’s meeting with Fred ‘at a party’; details of his mother’s birthplace were inaccurate (Blair says it was ‘Stornoway, an island in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides’); and her past as a servant went unnoticed. The Trumps themselves insisted Mary came to New York ‘on holiday’, but journalistic work by Martin Hannan for the Scottish newspaper, The National, told a very different story: of a young woman who is listed on the passenger lists for the SS Transylvania, crossing from Lewis to New York, as ‘occupation: domestic.’

Trump’s long list of biographers have neither known, nor, it seems, cared much about this matrilineal heritage. If they had, they wouldn’t just have noticed the hard work and ambition that these women showed, they would also have noticed his mother’s tendency to muddy the facts, to not be entirely comfortable with the truth. They might have noticed the strange fact of Mary living in Fred Trump’s family home a good seven months before they married, a very odd arrangement for an unmarried couple at the time. They might have noticed the contradictory census information: “Fred and Mary Anne Trump played fast and loose with the American authorities on their census return in 1940, stating that Mary Anne Trump was a naturalised citizen when records available to researchers show that she was not naturalised until 1942” (Hannan, The National).

Do these omissions matter? Some sources cite Trump’s mother as a woman in furs who would go round collecting nickels and dimes from the rented washing machines in the buildings they owned; others say it was Trump’s grandmother, Fred’s mother, who did this. Whichever woman it was, they cannot agree, but either way, the picture of a penny-pinching matriarch who liked to lord it over others is what emerges, and it surely matters whether this example was set by Mary Anne Trump or Elizabeth Christ Trump? Any biographer would do their best to establish the truth of such a visually juicy story – if they were writing about a father, or a grandfather, that is.

It seems that the history of the Trump women is left to those stereotypically ‘feminine’ ways of storytelling: gossip, anecdote, innuendo. Doubly put-down, first by their lack of place or status in the Trump story (when the Trump men could barely have survived without them); and secondly, by the refusal to verify what few facts we do know about them, the Trump women are rendered unimportant, irrelevant, marginalised. And yet, there is so much to learn from them. Donald J Trump is considered the laziest president of all, preferring to watch tv and play golf to analysing political documents – where did his mother, grandmother and greatgrandmother’s work ethic go? Was it corrupted by the playboy allure of glitzy New York r

eal estate deals?

And what about Trump’s attitude to race? His father employed a black chauffeur, but his mother never had black servants, and this was throughout decades when white domestic workers were in extremely short supply. Trump himself attributes his ‘love of showmanship’ to his mother in The Art of the Deal but can he attribute anything else to her? He’s known for not caring about the truth – numerous accusers have highlighted ‘lies’ he has told on Twitter. Did Mary Trump also know how to conceal certain personal facts like her naturalisation status? Did her family never know that she went to the US as a servant, or did they just never mention it?

And what about Trump’s attitude to race? His father employed a black chauffeur, but his mother never had black servants, and this was throughout decades when white domestic workers were in extremely short supply. Trump himself attributes his ‘love of showmanship’ to his mother in The Art of the Deal but can he attribute anything else to her? He’s known for not caring about the truth – numerous accusers have highlighted ‘lies’ he has told on Twitter. Did Mary Trump also know how to conceal certain personal facts like her naturalisation status? Did her family never know that she went to the US as a servant, or did they just never mention it?

There is much to be asked about those Trump women, and the legacy they have left on the man with the most important job in the world. But until women’s stories are consi

dered as important as men’s when it comes to biography and history, we will have to wait for those questions to come to the fore, never mind explore their possible answers. For the story of the Trump women follows a pattern set by many biographies of famous men which don’t consider the importance of wives, mothers, and grandmothers, leaving the stories of these women to be told elsewhere, if they are lucky.

Why the influence of women in a famous man’s life should be regarded as less important is revealing of a culture that still consistently underestimates women’s contributions, no matter what they may be.

For so dazzled are biographers by the stereotypically male life stories, the big deals or wartime experiences, the excessive drinking or multiple marriages, that there are no spaces in which to explore the part that women play. Only recently, for example, has Zelda Fitzgerald’s work and her artistic influence on F. Scott Fitzgerald, rather than their dysfunctional romantic relationship, really come to light; in this 200-year anniversary of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, many are still amazed to learn that she continued to write and publish books after her husband, the poet Shelley, died. Women tied to famous or great men, no matter how influential they are, or how much they achieve in their own right, are still subject to erasure and misunderstanding. They are still in the margins, still in the footnotes.

For so dazzled are biographers by the stereotypically male life stories, the big deals or wartime experiences, the excessive drinking or multiple marriages, that there are no spaces in which to explore the part that women play. Only recently, for example, has Zelda Fitzgerald’s work and her artistic influence on F. Scott Fitzgerald, rather than their dysfunctional romantic relationship, really come to light; in this 200-year anniversary of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, many are still amazed to learn that she continued to write and publish books after her husband, the poet Shelley, died. Women tied to famous or great men, no matter how influential they are, or how much they achieve in their own right, are still subject to erasure and misunderstanding. They are still in the margins, still in the footnotes.

Lesley McDowell is a writer, critic and editor. She has published two novels, The Picnic and Unfashioned Creatures, as well as book of literary non-fiction, Between the Sheets: The Literary Liaisons of Nine 20th Century Women Writers.

Lesley McDowell is a writer, critic and editor. She has published two novels, The Picnic and Unfashioned Creatures, as well as book of literary non-fiction, Between the Sheets: The Literary Liaisons of Nine 20th Century Women Writers.